High-level is the goal

Why should anyone care about low-level programming?

If you have heard of the Handmade community, you likely think we are about “low-level programming” in some way. After all, we are a community inspired by Handmade Hero, a series where you learn to make a game and engine from scratch.

We in the Handmade community often bemoan the state of the software industry. Modern software is slow and bloated beyond belief—our computers are literally ten times more powerful than a decade ago, yet they run worse than they used to, purely because the software is so bad. The actual user experience has steadily declined over the years despite the insane power at our fingertips. Worst of all, people’s expectations have hit rock bottom, and everyone thinks this is normal.

The Handmade crowd seems to think that low-level programming is the key to building better software. But this doesn’t really make sense on the surface. How is this practical for the average programmer? Do we really expect everyone to make their own UI frameworks and memory allocators from scratch? Do we really think you should never use libraries? Even if the average programmer could actually work that way, would anything actually improve, or would the world of software just become more fragmented?

I do believe, with all my heart, that low-level programming is the path to a better future for the software industry. But the previous criticisms are valid, and should be a serious concern for the Handmade programmer. So what is the connection here? What role does “low-level” play in a better future for software?

In 2019, a maker and YouTuber named Simone Giertz unveiled “Truckla”.

Simone wanted an Tesla pickup truck, but the Cybertruck was still just a rumor, and she was feeling impatient. So she did what any reasonable person would do, and decided to convert a Tesla Model 3 into a pickup truck.

The results speak for themselves. Truckla looks amazing, drives perfectly, and still functions as a modern EV. This is no small feat—obviously you cannot just cut the roof off a sedan and call it a pickup truck. She and her team had to ensure that the car was structurally sound, that it could still charge, and that the software still worked as intended. Truckla is an impressive feat of engineering that took genuine creativity and craftsmanship.

And yet, Truckla is still a pretty bad pickup truck! The bed size is small, it can’t haul much weight, and it’s likely much less efficient than a truck engineered from the ground up. If you were in the market for a pickup truck, you would not buy Truckla! (You probably wouldn't buy a Cybertruck either, but I digress.)

Truckla is an excellent execution of a flawed idea. If you want to build a good pickup truck, you have to start with the frame.

In the world of software, the equivalent of the "frame" is the tech stack. Software is shaped by programming languages, frameworks, libraries, and platforms in the same way that a car is shaped by its frame. If you convert a sedan into a truck, you will get a bad truck, and if you start with the wrong stack, you will get bad software. No engineering effort will be able to save you.

As an example, let’s look at a program that everyone has interacted with at some point.

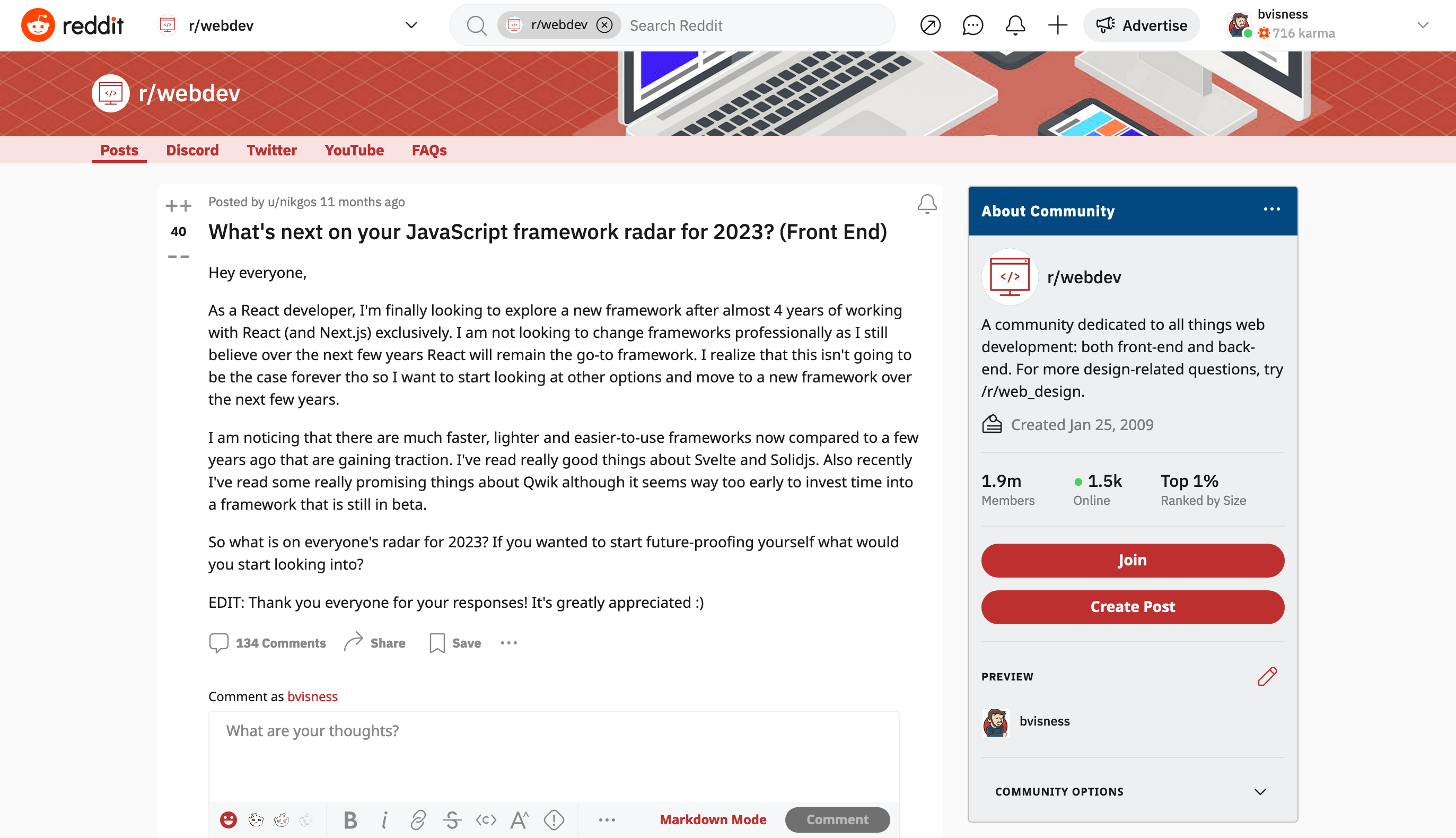

This is New Reddit. It is a new frontend they rolled out roughly a decade ago, and it is...not well-loved. Because so many people hate it, Old Reddit is still online, and this gives us a unique opportunity to compare two functionally identical pieces of software made a decade apart.

Back in 2023, I was experiencing horrible lag on New Reddit. The comment editor was sluggish, UI was slow to expand and collapse, and even hovering over a tooltip would cause a full-page hitch—all typical of modern software. Old Reddit, on the other hand, was a breath of fresh air—everything responded instantly. Aside from outdated aesthetics, Old Reddit was better in every way.

So here’s a thought experiment: How much work should it take to collapse a single comment?

This is a pretty easy question. All that needs to happen—all that should happen—is to hide or remove a few DOM elements, and update some text to say “collapsed”. A well-written Reddit frontend should more or less do exactly this. But let’s see what New Reddit did:

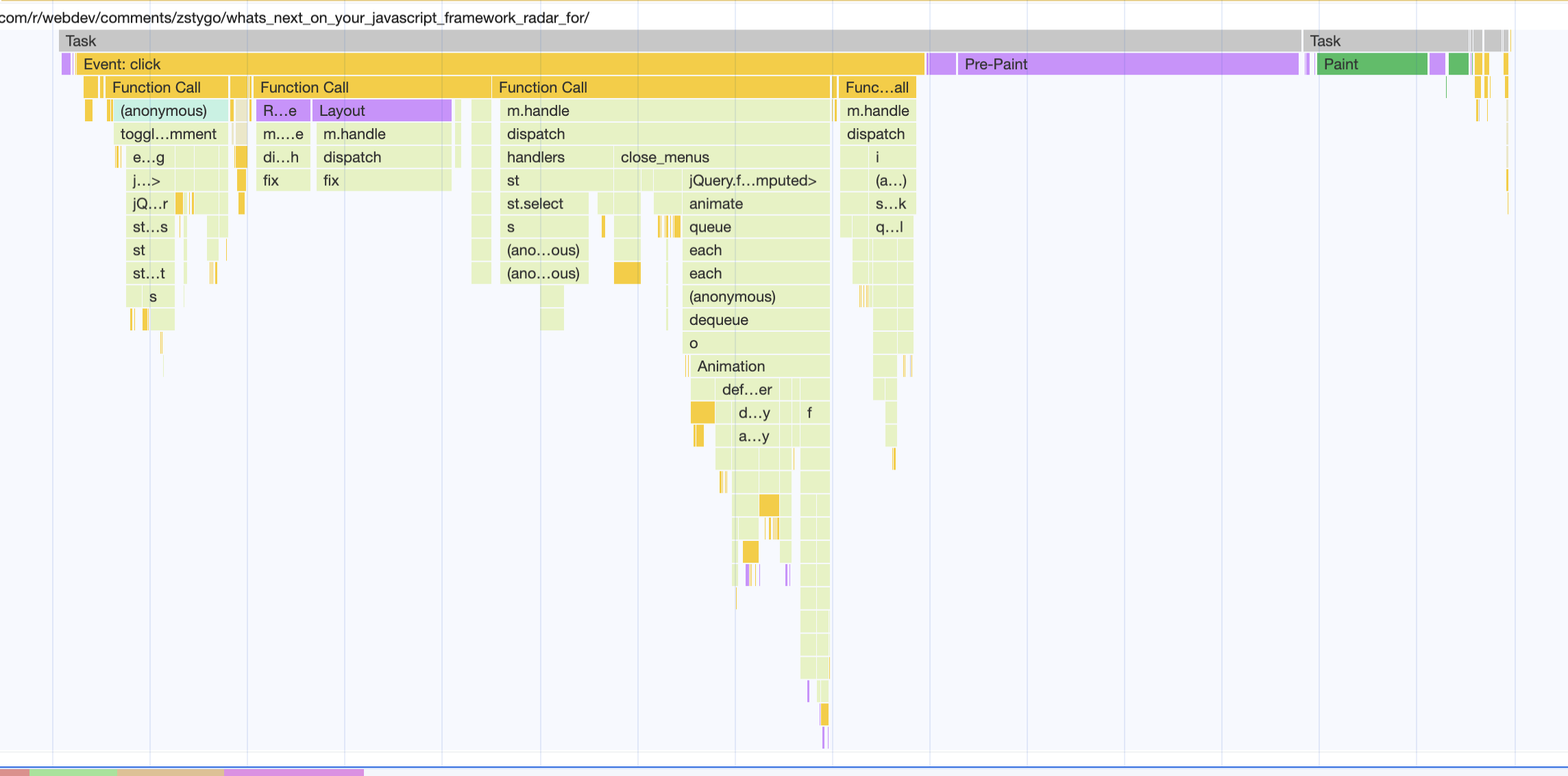

Gross. Call stacks thirty functions deep, layout computation in the middle of rendering, some kind of event or animation framework, and…hold on, is that jQuery?

My mistake, that’s actually a profile of Old Reddit. Here’s New Reddit:

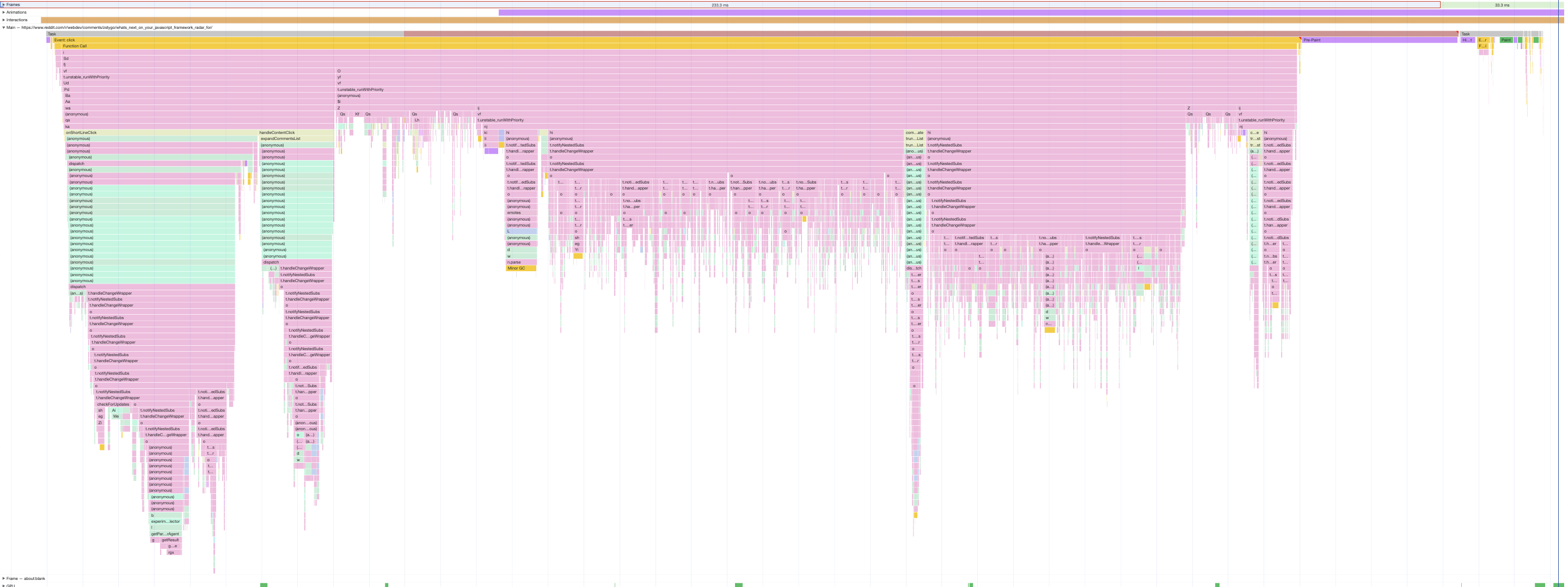

At the time, it took New Reddit almost 200 milliseconds to collapse a single comment. That is 200 milliseconds of pure JavaScript, with hardly any DOM work in sight. If you care about quality software, your jaw should be on the floor. It is a staggering amount of waste for what should have been a few DOM calls. And you feel it as a user: an ugly, intense hitch.

Old Reddit, on the other hand, did its work in about 10 milliseconds. That could be improved, but 10 milliseconds is totally fine. It feels responsive and keeps the site running at 60 frames per second. So Old Reddit is the clear winner here, with a UI 20 times faster than New Reddit.

So, we must pick up our jaws off the floor and ask the question: How on earth did we get here? Were New Reddit’s devs just stupid, lazy JS fanboys who would rather build Rube Goldberg machines than do their jobs?

Maybe tbh. But laziness alone doesn’t tell the whole story. The real problem with New Reddit was the stack it was built on.

So what was the Reddit stack? Back in 2023, New Reddit was a React app with Redux for state management. (These days they seem to have rewritten it in Web Components.) React and Redux of course sit atop the web platform: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. This platform is implemented by some browser engine, which then runs on some operating system, and finally on the user’s physical hardware (which is itself extremely complicated, but we have to stop somewhere).

At my last job, I worked on an application that used precisely this same stack. Our application was an employee scheduling program that allowed managers to create weekly schedules for hourly workers. In about 2016 we replaced our aging Backbone.js frontend with a new one written in React and Redux, presumably because it was a popular choice at the time.

As a result, I became intimately familiar with how a React+Redux app is constructed. I also spent a lot of time trying to improve the app’s abysmal performance. I lived inside the Chrome and React profilers, diligently tracking down slow functions and suppressing unnecessary React updates. We had a whole caching system for our Redux selectors, and I added logging to help us find selectors with a high cache miss rate. I built scripts to parse our source code and make graphs of our selector dependencies, so I could find places to split the app bundle into smaller pieces. Unfortunately, none of my work made much of a difference—performance continued to plummet as the app increased in complexity.

When you try to make a fast React+Redux app, you are constantly fighting the frameworks. These two libraries constantly do unnecessary work, and your job is to suppress that work until things run acceptably again. But sometimes the cure is worse than the poison: an expensive shouldComponentUpdate versus an expensive React re-render. Everything wants to update all the time, and as the app grows larger, the frequency and complexity of updates increases until there's no salvaging it.

New Reddit exemplified this perfectly: collapsing a comment would dispatch a Redux action, which would update the global Redux store, which would cause all Redux-connected components on the page to update, which would cause all their children to update as well. In other words, collapsing one comment triggered an update for nearly every React component on the page. No amount of caching, DOM-diffing, or shouldComponentUpdate can save you from this amount of waste.

At the end of the day, I had to conclude that it is simply not possible to build a fast app on this stack. I have since encountered many web applications that suffer in exactly the same way. Time and again, if it’s slow, it’s probably using React, and if it’s really slow, it’s probably using Redux. The stack is the problem. It’s the only reasonable conclusion.

Thankfully, React+Redux is not the only possible software stack. We can choose alternatives at every point:

- You could choose a different JavaScript framework. Perhaps you could use Vue, or Svelte, or SolidJS, since these have presumably had time to learn from React’s mistakes. Or, of course, you could ditch all the frameworks and just use the DOM APIs directly, especially if your application is mostly static like Reddit.

- You could use other browser APIs instead of HTML, CSS, and JS. You could use an alternative framework like Flutter, or you could build a custom UI stack in WebGL and WebAssembly. Building it yourself might sound crazy, but it’s been done successfully many times before—for example, Figma famously built their app from scratch in WASM and WebGL, and it runs shockingly well on very large projects. Google Docs and Google Sheets also use WebGL instead of HTML and CSS, and the apps themselves are written in Java and compiled to JS or WASM.

- You could build a native app! You could use a cross-platform framework like Qt, a game engine like Unity, an OS abstraction layer like SDL, or again just use the native APIs directly and build the rest from scratch. This is obviously the right choice for performance-intensive applications, and a valid option in general for developers who are serious about delivering a high-quality experience.

Together all these choices actually form a tree. Every node in this tree is a valid stack you could choose to build your software on. Most importantly, different choices in this tree will be better for different kinds of software, so being comfortable with many options allows you to make better choices for each problem you face.

Unfortunately, this is how I imagine the developers of New Reddit saw the tree:

There are not a lot of choices here. Critically, the best choice for them (direct DOM manipulation, like Old Reddit) was not even on the table. For whatever reason, I think they just didn’t even consider it as an option. Ew, icky, we can't just keep doing what Old Reddit did! We can't use jQuery!

Their view of the world was too high-level. If all you know is React, you have no choices—you can only use React, or meta-frameworks on top of React. But the lower level you can go, the more the tree opens up to you. Going lower level allows you to access other choices, and to recognize when another choice would be a better fit.

The first reason, then, that we care about low-level is that it allows us to make better choices. We can make better software by starting in the right place, with the right frame and the right stack. Low-level programming allows us to build trucks instead of Trucklas.

But…this isn’t really enough, right? The software industry will not be saved by a few programmers making better choices. It would help, to be sure, but it’s far from the answer.

This presents an uncomfortable question: What if there are no good options in this tree? What if none of these choices are actually good for the kind of software we want to make?

For example, what if your app wants direct access to the hardware, but you also want a cross-platform UI? What are your choices? You could use Qt, but it tends to feel very dated and has strong opinions about how you architect your software. Game engines would likewise be a strange fit for a lot of applications, offering plenty of rendering power but little for 2D UI. There are some relative newcomers like Flutter, but Flutter makes you buy into Dart, and we all know Dart is not the right tool for a performance-intensive application. So what do you do? There are no good choices on the market—you’ll have to build it yourself.

Our tree is top-heavy. If we survey the software development landscape today, we see an insane number of JavaScript libraries and frameworks, an ever-growing number of browser APIs, and very little development outside of browsers besides frameworks that are Web-compatible and therefore subject to the same constraints. If our tree was a real tree, it would look something like this—and this is not a healthy tree.

The analogy works even better, actually, when you consider how many branches are dead or dying. What is the lifespan of a JS framework these days? Two years? Five if you’re lucky? More likely, the developer will have vanished off the face of the earth within a month.

Do we really imagine that the future of the software industry is to grow this tree even taller? To build more on top? Frameworks on top of frameworks? Do we imagine that in the future we’ll still be using HTML and CSS for sophisticated applications, when they’ve clearly been the wrong choice for years? Do we imagine that we’ll continue to ship apps on top of browsers, on top of operating systems, when modern browsers are basically operating systems unto themselves?

If we keep building, this tree will collapse under its own weight. We need to prune it, and grow new branches from lower in the tree.

But who is going to do that? Who is going to build that future for the software industry?

It requires a particular type of person. They must have inherent drive and passion for innovation in software. But they also must have low-level knowledge. They need to be able to make different choices from those who came before, to explore parts of the tree that haven’t yet been explored.

The overlap between these circles is tiny. There are so few people who fit into both categories that we are just not seeing much innovation in that space. In fact, this image is pretty generous when you consider how few low-level programmers there are in general.

On the other hand, there are actually lots of people in the software industry with a drive to innovate. The problem is, they’re all making JavaScript frameworks.

They don’t possess the low-level knowledge required to actually make a significant difference. That’s just the reality: if you build from the top of the tree, all the important decisions have already been made for you. It's like painting a Truckla a different color—it will not make a difference!

So the second reason I believe low-level is critical to the future of the software industry is that it simply expands the circle. We can capture some of those people with the drive to innovate and equip them to actually innovate in meaningful ways. We need more people exploring this low-level space, and I know that for many people, low-level knowledge would open their eyes to possibilities they would never have dreamed of before.

Not everyone who makes their own text editor will have great ideas about the future of programming. Not everyone who makes their own compiler will have great ideas about programming languages. But some of them will. And it only takes a few of them to make a difference in the software industry.

So, to recap: the first reason we care about low-level is because low-level knowledge leads to better engineering choices. The second reason we care about low-level is because, in the long term, low-level knowledge is the path to better tools and better ways of programming—it is a requirement for building the platforms of the future.

But there is still one big problem with all of this: low-level programming today is absolutely terrible.

Low-level programming is so frustrating, and so difficult. The experience of low-level programming does not hold a candle to the experience of using high-level tools today—the very tools we see as a problem.

If I want to make a React app, I can simply Google “how to build react app” and I will find a beautifully-crafted web page with demos, installation guides, documentation, and resources to get me on my way. It has commands I can run to get an app up and running in five minutes. If I change a line of code in my editor, it refreshes immediately in my browser, shortening that feedback loop and making learning fun. And there is a wealth of other resources online: dev tools, libraries, tutorials, and more, making it easy for anyone to get up and running.

This is simply not the case for the low-level space. If you’re lucky, you can maybe find an expensive book or course. But more likely, you’ll just get a gigantic manual that lists every property of the system in excruciating detail, which is totally worthless for learning and barely usable as reference. And that’s if you’re lucky—there’s a good chance that you’ll only get a wiki or a maze of man pages, which are impenetrable walls of jargon. In some cases the only documentation that exists is the Linux Kernel Mailing List, and you can only pray that the one guy who can answer your question hasn’t flamed out in the past decade.

This isn’t just bad for beginners, it’s bad for everyone. If this is the state of low-level knowledge, how can we expect anyone to practice low-level programming, much less the wider industry?

And the story doesn’t end there, because low-level tools are terrible too. In a browser, I can open up the dev tools, go to Performance, click “Record”, and I will get a complete timeline of everything my application did. Every JavaScript function, every network request, every frame rendered, all correlated on a timeline so you can understand how everything relates. It is a developer’s dream, and it is a single click away! But the low-level space just does not have tools like this. There are a few decent profilers, but in most cases you just have to run a command-line program with some bizarre set of flags, pipe it through other tools, and then squint at a PDF or whatever.

The crazy thing is: there is no reason for this to be the case. We could absolutely have the same kind of “dev tools” for native development that we do for the web. We could have profilers that are actually designed to highlight useful info. We could have GUIs that show us network and file I/O, or inter-process communication. We could have interactive documentation and live reloading. We could have editor plugins and language servers to help beginners along. The raw capabilities are there. We're just waiting for someone with high-level sensibilities to come along and build the tools of our dreams.

But until we build that, why should we expect anyone to learn low-level programming? How can we expect them to?

So now we come back to Handmade, and what made Handmade Hero so special. Most programmers look at game engines and think that only a super-genius could write one—and the idea of making a game without an engine is lunacy. But Handmade Hero just didn’t care. Casey just sat down, showed you how to compile C, showed you how to put pixels on the screen, and before too long, you had a game. Not the most sophisticated game in the world, but a game nonetheless.

Handmade Hero shattered the barrier between low-level and high-level. Casey made a game, and he made an engine. The mystique was stripped away and replaced by an actual understanding of how games are made. Many people have the same reaction when they finally go through Handmade Hero: “Hey, this is not as hard as I thought!” It turns out you absolutely can make your own engine, despite the naysayers online.

I personally have found this to be true of so many “low-level” disciplines. “Low-level” programming is not impossible; in fact, in many cases, it’s simpler than the high-level web dev work I used to do! Today’s “high-level” frameworks and tools are so complicated and so poorly designed that they are harder to understand and work with than their low-level counterparts. But all the modern nonsense like Svelte, Symfony, Kubernetes—those tools have docs! They have dev tools! Because, for some reason, people are not afraid of them!

Low-level programming is artificially terrible. I really believe that. And I know that it doesn’t have to be this way.

So my final question about low-level programming is: why do we even call it “low-level”?

The intent of any “high-level” tool is to make it easier to express our intent as programmers. “High-level” tools abstract away difficult details so we can focus on what we really care about. And in many cases this has worked: we’ve seen it in the evolution of programming languages, in the proliferation of game engines, and yes, even in the development of the web.

But notice: this is not about where these tools are in the stack. It’s not about how many layers they’ve built on top of. “High-level” is about the expression of the programmer’s intent. The position in the stack is ultimately irrelevant if programmers can use it to achieve their goals.

What then does this mean for “low-level”? The conclusion is inevitable: the reason we call things “low-level” is because they are terrible to use. They are “low-level” because we do not use them directly! Because we sweep them under the rug and build abstractions on top, they become this low level that we don’t want to touch anymore!

Why are things “low-level” today? Because no one has made them high-level yet.

When I imagine a better future for the software industry, I don’t imagine one where everyone is making their own text editors, their own debuggers, or their own UI frameworks. Instead, I imagine a future where we have new “high-level” tools, built from lower in the stack. I imagine new tools that give the same high-level benefits we expect today, and in fact do more than the tools we have today, because they are freed from the constraining decisions of the past. We can build new platforms, new tools, and new libraries that learn from the past, but build on solid foundations instead of piling more on top.

For the developers who truly care about making high-quality software, tools built lower in the stack can be their superpower. These programmers can be equipped to fine-tune their software in ways the web could never allow. And for the lazy Reddit dev who would rather push some slop out the door for a paycheck? Hey, at least their slop can run on a simpler, smaller, more efficient platform. It’s still a net positive in the end.

The Handmade community is positioned right in the middle of that Venn diagram today. We have people with low-level expertise. We have people with a drive to make software better. Our job, then, is not to just write low-level code and feel smug for knowing how things work. Our job is to build a new high level for the rest of the software industry.

Low-level programming is not the goal unto itself. High-level programming—a new kind of high-level programming—is the goal, and low-level is how we get there.

This post is adapted from a talk I delivered to the Handmade community in 2023. The original talk can be viewed here.